Linux Memory Management

by Wenwei Weng

Linux memory management is a pretty complicated area. For the last few days I have debugging linux kernel soft lockup issue, and had a chance to revisit memory management in linux. I found it is actually very interesting.

Overview of Linux memory Management

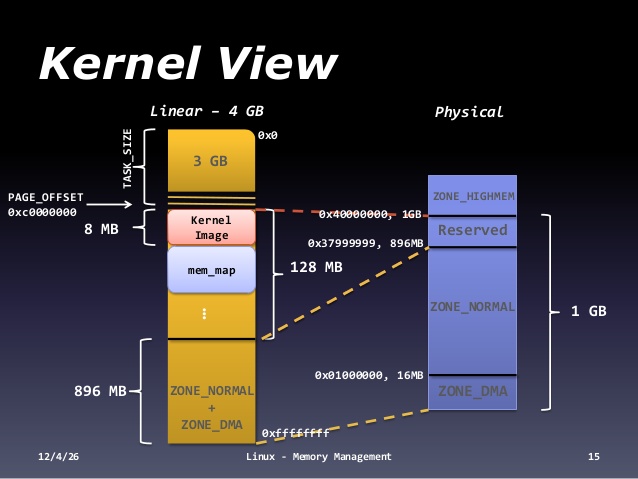

Linux has physical address and virtual address. For either kernel or user space program, it always uses virtual address for memory access. For each process, there is 1GB(kernel)/3GB(user space) address space split as shown in the above diagram. The kernel address space is 3GB - 4GB, the user space is 0 - 3GB.

Linux manages the memory by page, which is typically 4K bytes size.

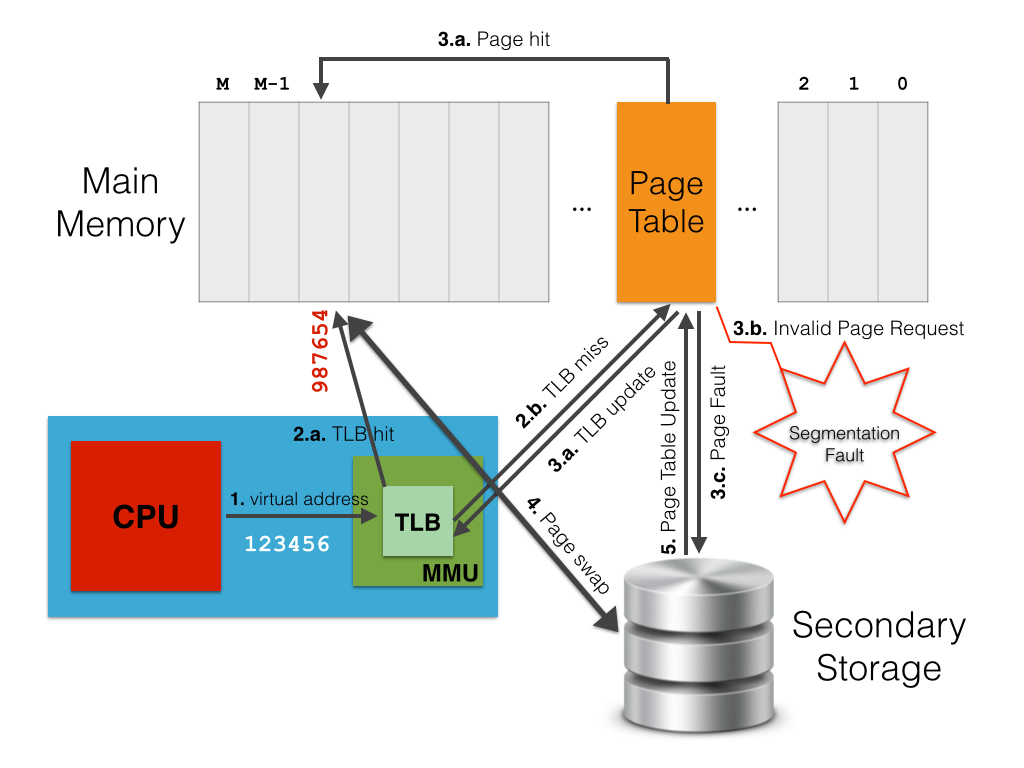

The modern processor has hardware to assist to trnaslate virtual address to physical address.

When a virtual address needs to be translated into a physical address, the MMU first searches for it in the TLB cache (step 1. in the picture above). If a match is found (i.e., TLB hit) then the physical address is returned and the computation simply goes on (2.a.). Conversely, if there is no match for the virtual address in the TLB cache (i.e., TLB miss), the MMU searches for a match on the whole page table, i.e., page walk (2.b.). If this match exists on the page table, this is accordingly written to the TLB cache (3.a.). Thus, the address translation is restarted so that the MMU is able find a match on the updated TLB (1 & 2.a.). Unfortunately, page table lookup may fail due to two reasons. The first one is when there is no valid translation for the specified virtual address (e.g., when the process tries to access an area of memory which it cannot ask for). Otherwise, it may happen if the requested page is not loaded in main memory at the moment (an apposite flag on the corresponding page table entry indicates this situation). In both cases, the control passes from the MMU (hardware) to the page supervisor (a software component of the operating system kernel). In the first case, the page supervisor typically raises a segmentation fault exception (3.b.). In the second case, instead, a page fault occurs (3.c.), which means the requested page has to be retrieved from the secondary storage (i.e., disk) where it is currently stored. Thus, the page supervisor accesses the disk, re-stores in main memory the page corresponding to the virtual address that originated the page fault (4.), updates the page table and the TLB with a new mapping between the virtual address and the physical address where the page has been stored (3.a.), and finally tells the MMU to start again the request so that a TLB hit will take place (1 & 2.a.).

In the process of page table lookup using virtual address, it uses three levels of translation:

As shown, in 1 32-bit virtual address, the first 10 bits are an index to page director, the next 10 bits are an index to page table, the last 12 bits is the offset to the page.

There are tools like “cpuid”, “perf” to find the cache size and TLB miss.

weng@weng-u1604:/$ cpuid -1 | grep TLB

cache and TLB information (2):

0x63: data TLB: 1G pages, 4-way, 4 entries

0x03: data TLB: 4K pages, 4-way, 64 entries

0x76: instruction TLB: 2M/4M pages, fully, 8 entries

0xb5: instruction TLB: 4K, 8-way, 64 entries

0xc3: L2 TLB: 4K/2M pages, 6-way, 1536 entries

L1 TLB/cache information: 2M/4M pages & L1 TLB (0x80000005/eax):

L1 TLB/cache information: 4K pages & L1 TLB (0x80000005/ebx):

L2 TLB/cache information: 2M/4M pages & L2 TLB (0x80000006/eax):

L2 TLB/cache information: 4K pages & L2 TLB (0x80000006/ebx):

weng@weng-u1604:/$ Memory Zones

The Linux kernel doesn’t consider all of your physical RAM to be one great big undifferentiated pool of memory. Instead, it divides it up into a number of different memory regions, which it calls ‘zones’

- ZONE_DMA: it is the low 16 MBytes of memory. At this point it exists for historical reasons; once upon what is now a long time ago, there was hardware that could only do DMA into this area of physical memory.

- ZONE_DMA32: it exists only in 64-bit Linux; it is the low 4 GBytes of memory, more or less. It exists because the transition to large memory 64-bit machines has created a class of hardware that can only do DMA to the low 4 GBytes of memory.

- ZONE_NORMAL: it is different on 32-bit and 64-bit machines. On 64-bit machines, it is all RAM from 4GB or so on upwards. On 32-bit machines it is all RAM from 16 MB to 896 MB for complex and somewhat historical reasons.

- ZONE_HIGHMEM: it exists only on 32-bit Linux; it is all RAM above 896 MB, including RAM above 4 GB on sufficiently large machines.

The zone information can be foundlike below:

weng@weng-u1604:~$ cat /proc/buddyinfo

Node 0, zone DMA 2 1 2 3 4 2 1 1 2 0 3

Node 0, zone DMA32 5839 5545 2339 1318 708 400 214 86 60 3 344

Node 0, zone Normal 797 694 577 360 238 144 50 28 12 0 0

weng@weng-u1604:~$ Kernel memory management

As previously stated, kernel manages memory per page, which is typically 4K bytes size. THe kernel provides one low-level API to allocate pages <linux/gfp.h>. The two core functions are:

- struct page *alloc_page(gfp_t gfp_mask, unsigned int order): Allocate 2 order pages and returns a pointer to the first page's page structure.

- void __free_pages(struct page *page, unsigned int order): free up pages allocated by taking page struct.

- unsigned long __get_free_pages(gfp_t gfp_mask, unsigned int order): it works same as above, except that it returns virtaul address

- void free_pages(unsigned long addr, unsigned int order): free number of page 2order starting from the provided virtual address.

- void *kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags): this takes number of bytes, instead of number of pages. It is a higher level than above two page allocation functions.

- void kfree(void *addr): free up the memory allocated by kmalloc().

- void *vmalloc(unsigned long size): same as kmalloc(), except that it only allocate the memory with contigutous virtual address, not physically.

- void vfree(void *addr): free the memory allocated by vmalloc().

Slab layer:

Allocating and freeing data structures is one of the most common operations inside any kernel. To facilitate frequent allocations and deallocations of data, programmers often introduce free lists. A free list contains a block of available, already allocated, data structures. When code requires a new instance of a data structure, it can grab one of the structures off the free list rather than allocate the sufficient amount of memory and set it up for the data structure. Later on, when the data structure is no longer needed, it is returned to the free list instead of deallocated. In this sense, the free list acts as an object cache, caching a frequently used type of object.

One of the main problems with free lists in the kernel is that there exists no global control. When available memory is low, there is no way for the kernel to communicate to every free list that it should shrink the sizes of its cache to free up memory. In fact, the kernel has no understanding of the random free lists at all. To remedy this, and to consolidate code, the Linux kernel provides the slab layer (also called the slab allocator). The slab layer acts as a generic data structure-caching layer.

The slab layer divides different objects into groups called caches, each of which stores a different type of object. There is one cache per object type. For example, one cache is for process descriptors (a free list of task_struct structures), whereas another cache is for inode objects (struct inode). Interestingly, the kmalloc() interface is built on top of the slab layer, using a family of general purpose caches.

The caches are then divided into slabs (hence the name of this subsystem). The slabs are composed of one or more physically contiguous pages. Typically, slabs are composed of only a single page. Each cache may consist of multiple slabs.

Each slab contains some number of objects, which are the data structures being cached. Each slab is in one of three states: full, partial, or empty. A full slab has no free objects (all objects in the slab are allocated). An empty slab has no allocated objects (all objects in the slab are free). A partial slab has some allocated objects and some free objects. When some part of the kernel requests a new object, the request is satisfied from a partial slab, if one exists. Otherwise, the request is satisfied from an empty slab. If there exists no empty slab, one is created. Obviously, a full slab can never satisfy a request because it does not have any free objects. This strategy reduces fragmentation.

The following diagram shows high level slab design.

Buffer, Cache memory

If you run “top” or “free” command, you will find there is some information about buffer, cache memory.

weng@weng-u1604:~$ free -lm

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 3951 1258 1768 27 924 2610

Low: 3951 2183 1768

High: 0 0 0

Swap: 4092 0 4092

weng@weng-u1604:~$ These are memory in-use, but consider to be free. Sounds weird? Check this site for a detailed explanation. kswapd plays a key role to reclaim those memory.

User space memory management

The user space memory allocation is very different from kernel space.

malloc provides access to a process’s heap. The heap is a construct in the C core library (commonly libc) that allows objects to obtain exclusive access to some space on the process’s heap.

Each allocation on the heap is called a heap cell. This typically consists of a header that hold information on the size of the cell as well as a pointer to the next heap cell. This makes a heap effectively a linked list.

When one starts a process, the heap contains a single cell that contains all the heap space assigned on startup. This cell exists on the heap’s free list.

When one calls malloc, memory is taken from the large heap cell, which is returned by malloc. The rest is formed into a new heap cell that consists of all the rest of the memory.

When one frees memory, the heap cell is added to the end of the heap’s free list. Subsequent mallocs walk the free list looking for a cell of suitable size.

As can be expected the heap can get fragmented and the heap manager may from time to time, try to merge adjacent heap cells.

When there is no memory left on the free list for a desired allocation, malloc calls brk or sbrk which are the system calls requesting more memory pages from kernel.

Now there are a few modification to optimize heap operations.

- For large memory allocations (typically > 512 bytes, the heap manager may go straight to the OS and allocate a full memory page.

- The heap may specify a minimum size of allocation to prevent large amounts of fragmentation.

- The heap may also divide itself into bins one for small allocations and one for larger allocations to make larger allocations quicker.

- There are also clever mechanisms for optimizing multi-threaded heap allocation.

Debug tools:

- top

- vmstat

- pmap

References:

- Linux Kernel Development by Robert Love.

- http://www.eqware.net/Articles/CapturingProcessMemoryUsageUnderLinux/index.html

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/sysctl/vm.txt

- http://www.linuxatemyram.com/

- http://linoxide.com/linux-command/linux-vmstat-command-tool-report-virtual-memory-statistics/

- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/8367001/how-to-check-heap-size-for-a-process-on-linux

- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/3479330/how-is-malloc-implemented-internally

Subscribe via RSS